Weight Control and Metabolic Health: A Scientific Overview

Introduction

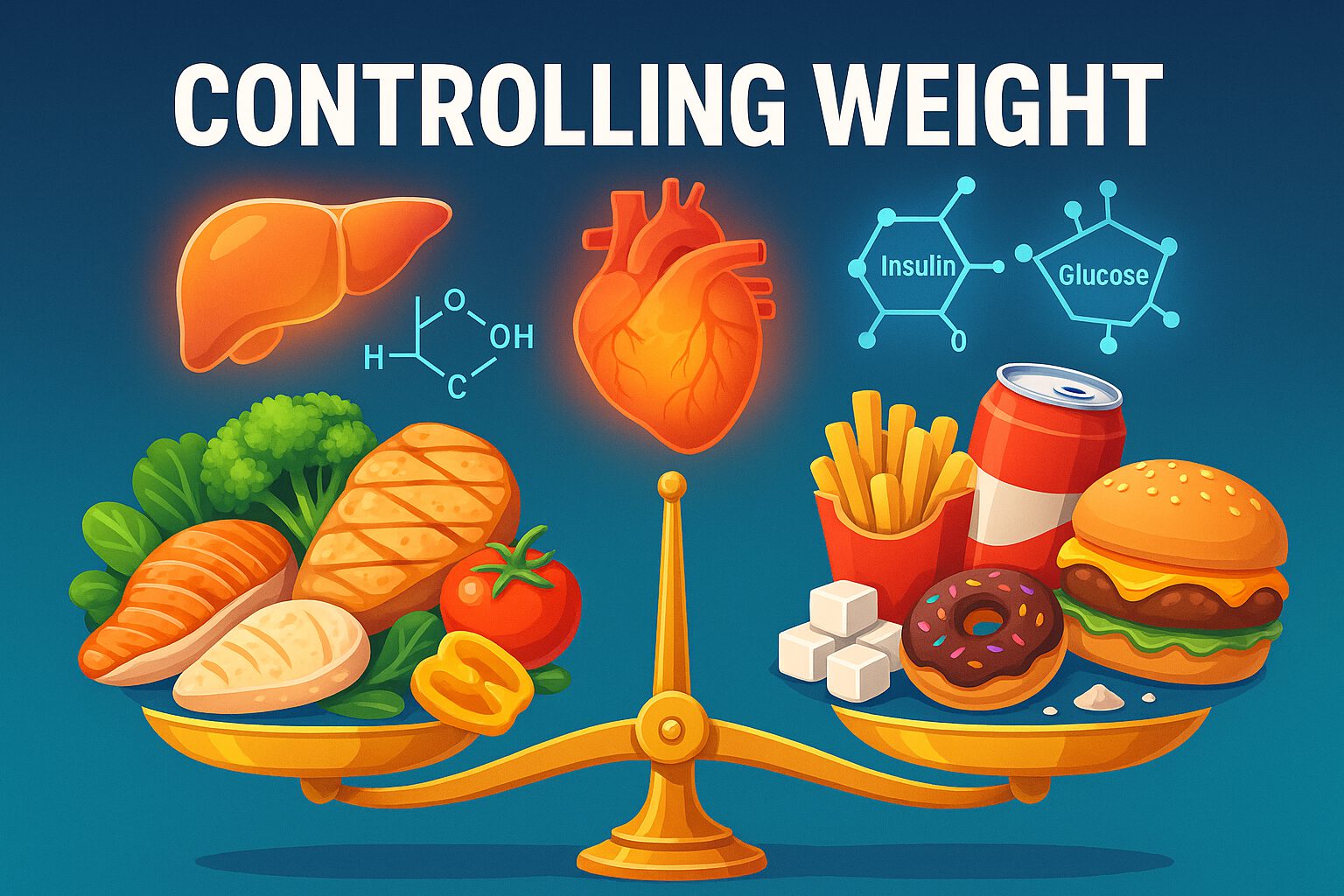

Weight control is central to preventing chronic diseases, maintaining metabolic health, and improving overall well-being. The rise in obesity and related disorders such as type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers can be traced to changes in dietary patterns, sedentary lifestyles, and disruptions to circadian rhythms. This article presents a comprehensive, science-based examination of how diet, physical activity, hormonal regulation, and environmental factors contribute to weight control, with insights from leading research in nutrition, metabolism, and endocrinology.

1. The Biochemistry of Weight Regulation

a. Energy Balance and Macronutrient Composition

Weight is regulated by the interplay between caloric intake and energy expenditure. However, calories from protein, carbohydrates, and fats differ in their metabolic fate and hormonal impact:

- Carbohydrates increase insulin secretion, promoting glucose uptake and fat storage. Simple sugars and refined carbs are especially lipogenic (fat-producing).

- Fats have a minimal effect on insulin but are energy-dense and may promote weight gain when overconsumed.

- Proteins increase thermogenesis and satiety. They stimulate glucagon and reduce ghrelin, making them more metabolically favorable in weight-loss diets.

b. Hormonal Influence

- Insulin: Central to fat storage. Chronically elevated insulin promotes lipogenesis and inhibits lipolysis.

- Leptin: Signals satiety; resistance leads to overeating.

- Ghrelin: The hunger hormone, increases before meals and decreases after eating.

Research shows that weight gain is not merely about calorie excess but also about hormonal and metabolic dysfunction (Lustig, 2006).

2. The Role of Diet in Weight Control

Low-Carbohydrate and Ketogenic Diets

Studies show that reducing carbohydrates particularly refined sugars lowers insulin levels and promotes fat oxidation. Ketogenic diets have been linked to:

- Reduced appetite due to ketone bodies (Volek & Phinney, 2011)

- Improved insulin sensitivity

- Enhanced mitochondrial function

Mediterranean Diet

Characterized by high intake of vegetables, legumes, olive oil, fish, and whole grains, the Mediterranean diet is associated with lower obesity and cardiovascular risk (Estruch et al., 2013).

Plant-Based Diets

Vegetarian and vegan diets, when well balanced, lead to weight loss due to lower energy density, higher fiber intake, and better insulin sensitivity (Barnard et al., 2005).

Time-Restricted Eating

Aligning food intake with circadian rhythms improves metabolic parameters. Eating within a 6–10-hour window has been shown to reduce weight and improve blood sugar control (Panda, 2020).

3. The Impact of Overweight and Obesity on Health

- Cardiovascular Disease: Excess weight increases blood pressure, cholesterol, and inflammation.

- Type 2 Diabetes: Fat accumulation in the liver and pancreas impairs insulin signaling.

- Cancer: Obesity is linked to breast, colorectal, liver, and pancreatic cancers via chronic inflammation and altered hormone levels.

- Neurodegeneration: Adiposity-driven insulin resistance and oxidative stress affect brain health.

4. Physical Activity and Energy Expenditure

Regular exercise enhances energy expenditure, preserves lean mass, and improves mitochondrial efficiency. Aerobic exercise burns calories, while resistance training increases resting metabolic rate by building muscle mass (Booth et al., 2002).

5. Environmental and Behavioral Factors

- Sleep Deprivation: Disrupts leptin and ghrelin, promoting hunger and insulin resistance.

- Stress: Activates cortisol, encouraging abdominal fat storage.

- Ultra-Processed Foods: High in sugar, fat, salt, and additives that impair satiety and alter gut microbiota (Monteiro et al., 2019).

6. Weight Loss Strategies: What Works?

- Personalization: Tailoring diets based on insulin sensitivity, genetics, and microbiome.

- Sustainable Change: Behavior modification and habit formation are key to long-term success.

- Combined Approaches: Diet, physical activity, sleep, and stress management must align.

Conclusion

Weight control is a complex interplay of biological, behavioral, and environmental factors. It requires more than calorie counting understanding hormones, food quality, circadian biology, and sustainable habits are crucial. A well-formulated, whole-food diet coupled with regular activity and stress control can significantly improve metabolic health and prevent chronic disease.

Key References:

- Lustig RH. (2006). Childhood obesity: behavioral aberration or biochemical drive? Reinterpreting the First Law of Thermodynamics. Nature Clinical Practice Endocrinology & Metabolism.

- Volek JS, Phinney SD. (2011). The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Living.

- Estruch R et al. (2013). Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. New England Journal of Medicine.

- Barnard ND et al. (2005). A low-fat vegan diet and body weight and lipid levels in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care.

- Panda S. (2020). The Circadian Code. Rodale.

- Monteiro CA et al. (2019). Ultra-processed foods, diet quality, and health using the NOVA classification. Public Health Nutrition.

- Booth FW et al. (2002). Waging war on physical inactivity: using modern molecular ammunition against an ancient enemy. Journal of Applied Physiology.

This article is part of The Life Lens series exploring the intersection of science, nutrition, and health for lifelong vitality.